|

040206

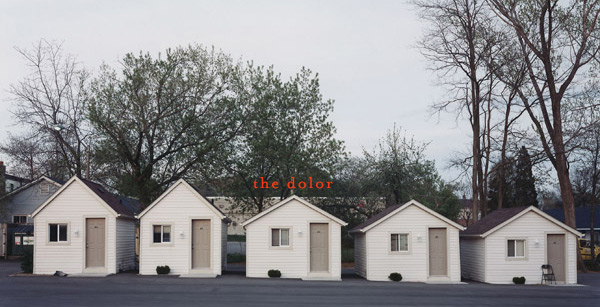

I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils,

Neat in their boxes, dolor of pad and paper-weight,

All the misery of manila folders and mucilage,

Desolation in immaculate public places,

Lonely reception room, lavatory, switchboard,

The unalterable pathos of basin and pitcher,

Ritual of multigraph, paper-clip, comma,

Endless duplication of lives and objects.

And I have seen dust from the walls of institutions,

Finer than flour, alive, more dangerous than silica,

Sift, almost invisible, through long afternoons of tedium,

Dropping a fine film on nails and delicate eyebrows,

Glazing the pale hair, the duplicate gray standard faces.

-Theodore Roethke

My grandfathers had the best offices. They were in factories, shipping plants, warehouses. Everything was so open-the dull sheens of gunmetal desks and file cabinets, the clatter of typewriters echoing in the joists of impossibly high ceilings, the tired smiles of middle-aged receptionists. Often there was cigarette smoke, and curly-edged color photographs fading in the bright sunlight that cut through the impossibly fat tapes of the window blinds.

Pops was the foreman of the mill next door, and the front offices of the mill were encased in tiles of plate glass and wood veneer as smooth and shiny as a full-fashion stocking. It was golden, glowing inside, the light refracting through the windows and bouncing off the folds of my grandfather's short sleeve oxford shirt, his clip-on tie.

He came home for lunch each day, walked across the pebbly asphalt of the parking lot and the thin strip of grass growing beside the carport. Sometimes he would walk down to the lunch counter at Surry Drug and bring us back grilled cheese sandwiches, still warm, wrapped in damp wax paper. If I was good, he would walk me back across the lot with him. The sun would be high in the sky. We would go out onto the floor and he would introduce me to countless Normas and Bettys and Lorenes. The knitting machines were medicine green and huge. The women had plaid blouses and impossible hair. It was hard to hear them when they said hello.

There was a glass foyer in Poppie's office. I think there was a plant and maybe a chair in it. And an ashtray, one of the standing kind. I can't remember the receptionist's name; she was older but she didn't dress like it. She had hair and nails and miniskirts. Poppie always picked on her, but in a nice way, the way you do when you really like someone but don't necessarily respect them.

I liked the creaking white enamel stove in the kitchen and the college boys in overalls and gloves who would come in from the warehouse to get a sip of water. I liked how the noises came from all directions: the scraping forklift in the warehouse, the loud salesmen with their wrinkled plaid jackets in their wood paneled offices, my grandfather calling me to come with him so we could go get pizza at a truck stop near a strip club on Wilkinson Boulevard.

My office is beige and very quiet. All I can hear is the repetitive shriek of the stockroom guy and his packing tape. My email blinks. I can see the park at the end of the air shaft. It's as big as my thumb is long. There's enough light to look into the offices across the airshaft, but not much. Still, sometimes I spy on them. At lunch, I walk through the southeastern corner of the park, smelling the horses and watching them stop to piss in the street, their dull and nubby coats barely reflecting the glints of light that spark off the scaffolding.

|

|